A safe and stable home is an essential requirement for a decent life. It offers a vital foundation for health, education, and the opportunity to work. For those who own their home, it is also often their greatest financial asset. Yet for the 70 percent of the world’s population with an income of less than $3,000 per year, the options for housing finance remain scarce and largely informal.

In the developed world, housing finance is synonymous with mortgage lending. It is a key element of the economy and the banking sector. In developing countries, mortgage markets tend to be shallow and frail, hampered by political and economic instability and weak legal regimes. In richer countries, properties backed by mortgages account for an average 40 percent of gross national product. In low-income countries, the figure is less than 1 percent.

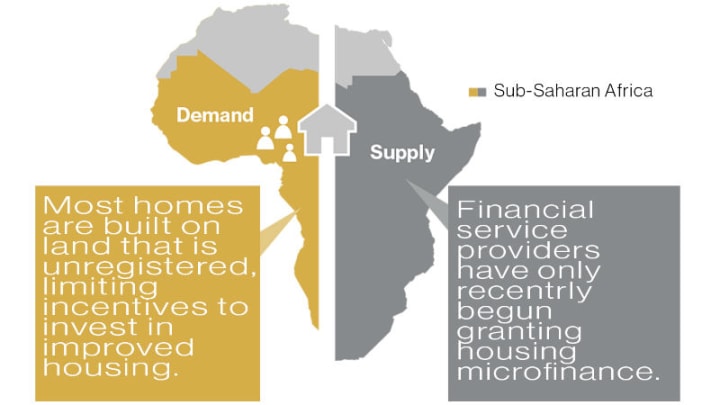

There are numerous impediments to getting a mortgage in the developing world. Banks limit mortgages to borrowers with stable, documented earnings and very often only the formally employed are granted a loan. The requirement of a down payment and the costs and complications associated with registering mortgages are major constraints, as is gaining formal title to a property when land registries are faulty and the legal complexities are many.

Micro-finance as a solution to improved health, education, and work

Housing microfinance offers a way around these obstacles. It applies the principle of microlending for small, grassroots enterprises — originally pioneered by the Grameen Bank — to housing. Loans ranging from $500-$2,500 are typically offered for periods of 12-36 months. In line with other microfinance loans, interest rates are in the range of 12 to 25 percent.

“Housing microfinance aims both to achieve a profit and make the planet a better place, by helping low-income households gain more of a stake in the economy.”

— Kevin Chetty, director for Europe, Middle East, and Africa at the Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter, Habitat for Humanity International

This approach acknowledges the fact that low income families, because of their limited resources, are forced to build or renovate homes incrementally. This progressive process may take several years or even decades, and entail acquiring land, building an initial structure, and following with a series of expansions and improvements.

Financial institutions that have ventured into housing microfinance have found it to be a very popular product with their clients, with many especially drawn to the positive impact on clients’ well-being. They have also experienced quick uptake and strong performing portfolios. It has been profitable.

Microfinance at work

Letshego Kenya, part of a financial services company operating in 11 African countries, initially focused on microenterprise lending. Noticing the booming market for urban rental housing, it began directing its housing loans to this sector in 2012. Just over 50 percent of its loan portfolio is now in housing.

Kenya Women Microfinance Bank and Centenary Bank in Uganda collaborated with Habitat for Humanity on the “Building Assets, Unlocking Access” project, a partnership between the Mastercard Foundation and Habitat’s Terwilliger Center for Innovation in Shelter. It developed housing microfinance products for people living on $5-10 per day, and importantly accepted customary land ownership as a legitimate claim of secure tenure.

KWFT’s Nyumba smart loan portfolio, aimed at women microentrepreneurs living in rural and semi-urban locations, has surged from 1,061 loans in April 2015, when pilot testing concluded and national rollout began, to 26,887 loans as of June 2017.

The CenteHome loan provided by Centenary, an established commercial bank in Uganda, is now undergoing a staged rollout, with 47 branches offering the product as of October 2017 and 3,500 loans taken out.

Within the 2016-17 State of Housing Microfinance: Understanding the business case for Housing Microfinance study, we found that 75 percent of institutions offer housing microfinance products to new clients. Data collected within the same report show that the contributions of housing microfinance products to profitability, which average 14.5 percent, are comparable to those of consumption loans (12 percent) and other business loans (17 percent).

The sector is still relatively new, but already the scope for expanding the provision of housing microfinance in sub-Saharan Africa is clearly very great indeed — and to the financial institutions that understand the opportunity, it is also very attractive.

Housing shortages and poor housing are all too common among the predominantly rural-based populations. Rapid urbanization is stretching very limited supplies of adequate housing and urban land. Yet that same expansion reflects the fact that African economies are among the fastest growing in the world. Investors are therefore showing increased interest in housing opportunities among the lower-middle income sectors.

Cyprian Asiimwe, a typical client, received a CenteHome loan of $690 and used it to purchase roofing, windows, and doors to complete the construction of his house. He has monthly repayments of $35 for two years. When he finishes repaying this loan, he plans to try to earn more money, add it to savings, get a new loan, and build a bigger house. “I don’t want to stay in a small house,” he told Habitat for Humanity when we interviewed him for our microfinance clients profile study in Uganda in May 2017.

His case, and indeed the way he sees financing as a way of improving his home, is encouraging. The pressing demand for housing microfinance is evidenced by the rapid uptake and high repayment performance that financial service providers have experienced. Housing microfinance aims both to achieve a profit and make the planet a better place, by helping low-income households gain more of a stake in the economy. That should in turn ease some of the strain on health and education services, allowing development practitioners to concentrate more on core issues within those disciplines, rather than coping with the effects that bad housing often has on educational performance and well-being.

Our big practical takeaway from developing microfinance products in East Africa is twofold: There are profitability drivers and outcomes, and there are nonfinancial drivers and outcomes. The success of a housing microfinance portfolio is founded on financial institutions’ ability to develop a product that is as much about portfolio diversification as it is about improving living standards among poor households.

Looking ahead, as sub-Saharan Africa’s financial services industries continue to grow and mature, housing microfinance is likely to become a mainstream offering. The burgeoning sector offers hope that Africa’s considerable housing problems can, over time, be addressed.

For more information about Habitat for Humanity’s work on micro-finance, click here.

About the author

-

Kevin Chetty

Kevin Chetty has over 20 years of combined experience in senior and executive level management in the financial services arena supporting low income households across Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. As the regional director for Habitat for Humanity, he supports financial inclusion by developing innovative and sustainable housing solutions for low income households.